Adam Au @Executive Sports Challenge

2025/10/14 - 2026/04/01

The form is not published.

About the Campaign

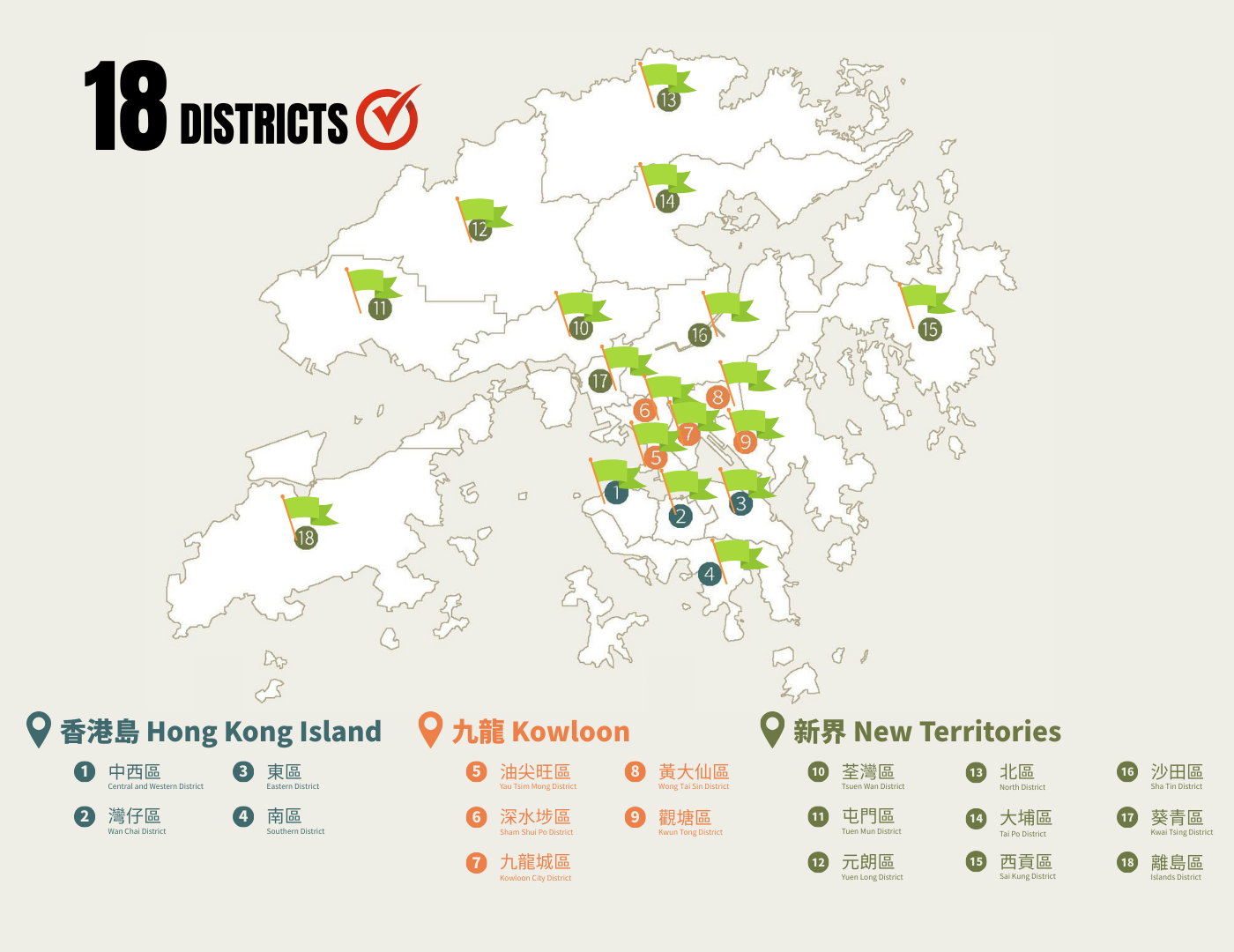

With the return of our IHKSports Executive Sports Challenge, we are thrilled to introduce our new challenger – Mr. Adam Au!

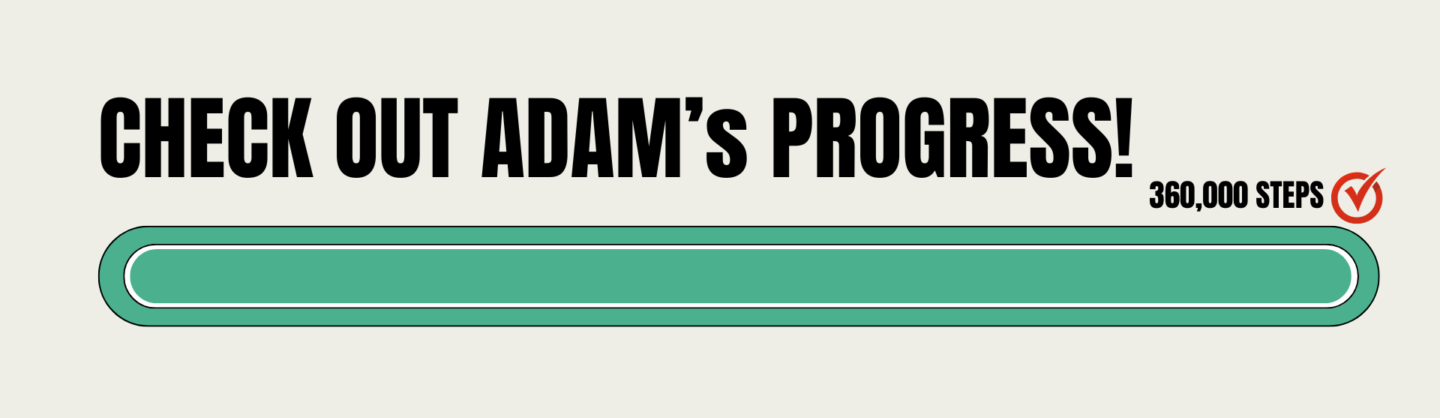

As a health advocate, Adam has chosen to embark on a uniquely personal and profound challenge: to walk 360,000 steps across all 18 districts of Hong Kong in just 90 days. His journey, “18 Districts in 90 Days,” is a powerful amplification of the Department of Health’s “10,000 Steps a Day” campaign, taking a well-known wellness goal and transforming it into an epic urban exploration for social good.

Adam shares, “Walking has always been my favorite form of exercise—simple, grounding, and a great way to experience the real Hong Kong. This challenge is about setting a personal goal to explore both familiar places and hidden gems, one step at a time. It’s a reminder that movement and discovery go hand in hand, and that there is immense beauty right outside our doors—rain or shine.

Progress in walking, much like in life, isn’t about speed; it’s measured in consistency and perspective. You don’t have to conquer the city to know it; you just have to keep moving through it with your eyes and heart open. Through this journey, I hope to push my own limits for a greater cause and inspire others to find their own path to wellness and wonder.”

A Glimpse from His Journey:

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 1 challenge in Central & Western District!

Day one felt like a homecoming. I started in Kennedy Town, slipped past the tram terminus and the old piers, and traced the waterfront to Sun Yat Sen Memorial Park before looping back. Finished with a gelato near the new Kennedy Town Praya street sign. Typhoon signal 3 was up, the air thick with late‑summer heat, and the promenade wore that pearly, wind‑rippled light Hong Kong gets before a squall. It didn’t stop me. If anything, the weather sharpened the edges—salt in the air, gulls riding crosswinds, runners bargaining with the clouds.

I used to do this at lunch, obsessively, counting steps like beads on a string—in my worn‑and‑torn leather shoes, no less. Treadmills never stuck; a moving belt feels like a half‑truth. Pavement gives you context. Streets have memory. Out here, the old and new keep talking to each other. You feel it in Western District—in warehouses turned cafes, tramlines under glass towers, and a distant hint of the new Kai Tak Sports Park across in Kowloon, glimpsed between hoardings and skyscrapers. Scaffolding and cranes along the harbourfront sketch a future against a skyline that doesn’t sit still.

The harbour did its best impression of proximity. Kowloon felt close enough to touch—ferries stitching the distance, container ships idling, the water shifting from slate to steel to green. It’s the kind of view that shrinks your world and enlarges it at the same time. This is my home. Love it, plain and simple.

People ask why I like walking. The answer is unromantic and true: it’s the easiest, most soothing way I know to reset. One foot in front of the other, Audible in my ears, a steady drumbeat of steps that makes room for thought without demanding it. Progress measured, not rushed. Much like life: you don’t have to conquer the city to know it; you just keep moving through it.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 2 challenge in Kwai Tsing District!

Kwai Tsing, thrum and graft

Started at Kwai Fong Station and let the morning spill me into Kwai Chung Plaza—my favorite hangout. Covid or not, this place is always packed: snack stalls and old‑school fish balls, escalators jammed, bubble‑tea sugar haze, sneaker shops stacked to the ceiling, aunties negotiating over phone cases like futures traders. I cut through to the lobby, glowing with posters and popcorn salt, then slipped back to street level where delivery trolleys ticked across tiles like metronomes.

Kwai Tsing wears its work on the surface. You feel it in container yards shouldering the horizon, flyovers ribbing the sky, and the steady tide of shift changes. I took the footbridges, elevated walkways stitching over Castle Peak Road, a river of traffic underfoot. Rails and roads braided around me—moving parts you usually blur past from a car window. A vantage point I’d never bothered to stop and appreciate.

I kept it flat and aimed for the water—the Rambler Channel promenade—industry on one side, quiet on the other. Fishermen with patient lines. Joggers pacing the railings. The water doing its slate‑to‑green mood shift. Stonecutters Bridge pulls your eye whether you want it to or not, that elegant span threading container ships and tug wakes.

Across the channel, the towers of Tsing Yi keep watch, trucks flashing by on the viaduct like quick thoughts. The promenade isn’t perfect—poignant smells drift in places, and the nearness of the Tsuen Wan Slaughterhouse throws a stark, ironic contrast against the postcard bridge. Industry is not just backdrop here; it’s in the air.

I looped back to Kwai Tsing Theatre and a small scoop of ice cream as reward. The foyer felt like a civic heartbeat—posters for Cantonese opera next to contemporary dance, teenagers rehearsing steps in the glass, ushers comparing notes about a sold‑out weekend. I love these places: the city’s nerve endings, where logistics make room for culture and the day’s exhale happens under stage lights.

Why walk here? Same answer as always: it resets the dial. One foot, then the next; the hum of buses, the click of trolley wheels, a bridge breeze cutting through diesel heat. Audible in my ears until the street took over and I hit pause to let the ambient thrum do the talking. Progress measured, not rushed. A district usually seen from an expressway suddenly becomes legible at 5 km/h.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 3 challenge in Sham Shui Po District!

Third entry: Sham Shui Po, the old vs. the new

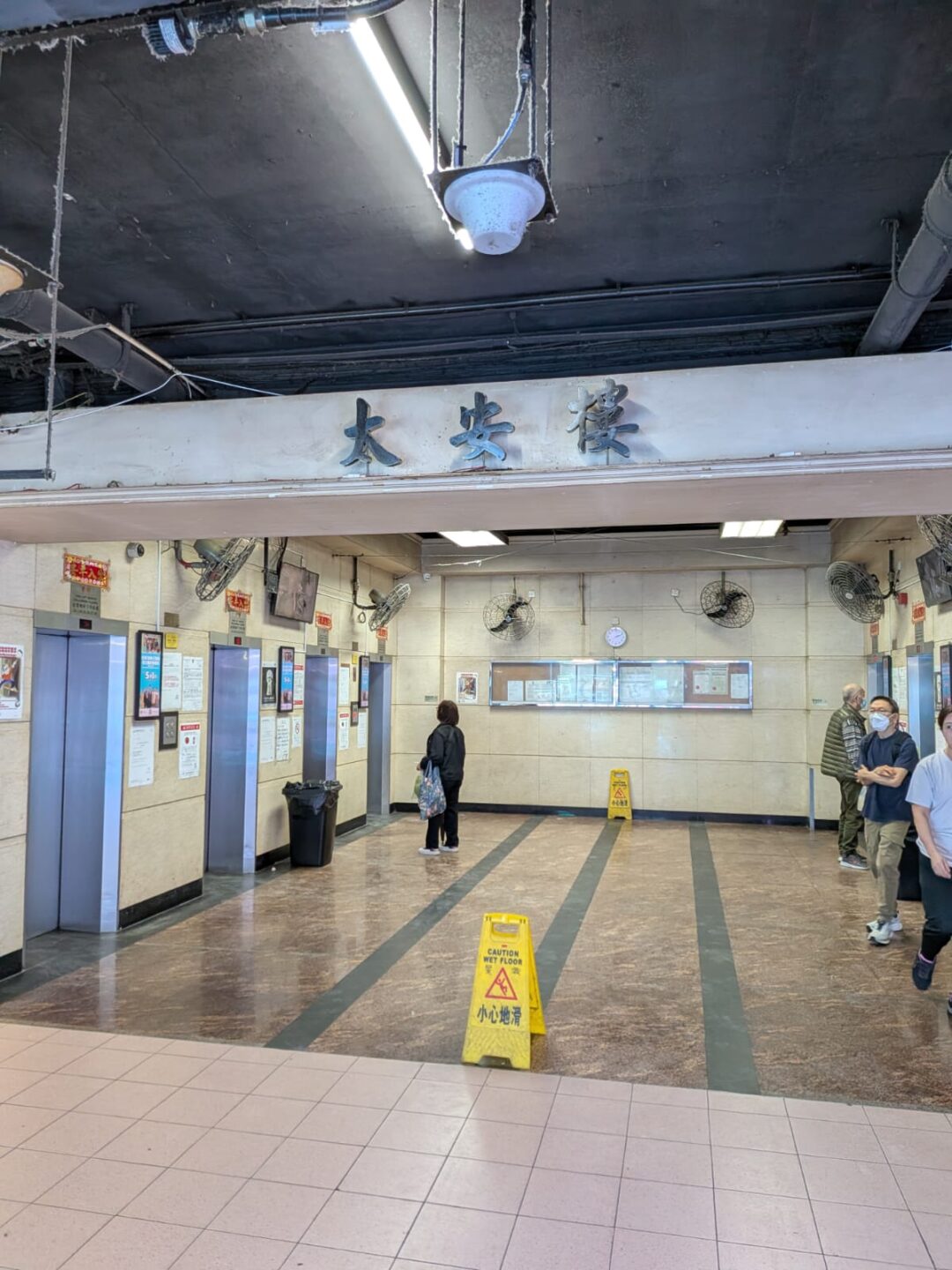

Started at Lai Chi Kok—a place that still feels personal because it is. I grew up here. Mornings meant schoolbags and bakery trays; weekends meant plastic stools, soy milk, and the clatter of dim sum lids. The blocks around the station were my first map—footbridges as shortcuts, back lanes as playgrounds, lift lobbies as echo chambers. Even now, the smell of steamed rice rolls or a whiff of engine oil pulls me straight back.

I took Castle Peak Road, that busy industrial spine where the old meets the new. Low‑rise walk‑ups shoulder next to fresh single‑tower inserts; scaffold and signage knit the gaps. Gentrification moves here step by step, but it hasn’t stripped the charm. The textures hold. Metal shutters wear hand‑painted numbers, tailors post tape‑measure hours, and above it all, new glass tries to learn the light.

I passed the Hong Kong Spinners Industrial building—a concrete witness to the garment industry’s rise, wobble, and reinvention. Brick, lintels, and long windows that once measured work by daylight. Decades of textiles in those walls; if you pause on the pavement, you can still hear the mill’s ghost rhythm under the traffic.

I cut through to the old arcades—Golden and its neighbors—time‑capsules that refuse a full handover to digital. Solder smoke and CRT ghosts in the mind’s eye; parts bins neat as apothecaries. Then onto Apliu Street—Hong Kong’s electronics heaven—buzzing like a living catalog: stalls stacked with every phone case known to humankind, radios and lenses laid out like chess pieces, cables coiled like noodles, shopkeepers calling specs in quick Cantonese.

Sham Shui Po wears the city’s working memory: secondhand stalls, pattern shops, fabric alleys, new cafes daring to soften the edges. A place where utility meets improvisation. Signboards layer like palimpsests; neon survivors blink alongside LED. You can read decades in a single block.

I drifted toward West Kowloon Centre, the weekend magnet—remittance counters, budget salons, racks of snacks and spices—where foreign workers gather for a good deal and a taste of home. Laughter in a dozen languages. Phones out, stories traded, bags of groceries slung like trophies.

Why walk here? Because this is Hong Kong without a filter. The city’s heartbeat comes through at human speed—barter and banter, repairs and reinvention. You learn what stays, what shifts, and how both can coexist on the same street.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 4 challenge in Yau Tsim Mong District!

Fourth entry: Tsim Sha Tsui → Mong Kok, along the spine

“The street is the river of life of the city, the place where we come together.” — William H. Whyte

Nathan Road is Hong Kong’s pulse. During Covid I watched it go hollow: neon without a crowd, taxis without fares. Now it’s back, packed, humming again.

I started at Ocean Terminal and skipped the postcard stops such as the Clock Tower and Victoria Dockside, letting the harbour sit in the periphery. I drifted toward the start of Nathan Road, step by step. I passed the promenade edge and the gate of Kowloon Park, resisting the shortcut through green. I wanted the street. Along the promenade, those shops with wry, old‑school English names still linger, selling fashion made elsewhere under imperial monikers. Alexander III sits next to Caesar, a faint echo of colonial Hong Kong.

Jordan to Yau Ma Tei is my old school run. Parts feel held in amber: the same corners, the same snack smells, the same bus‑stop choreography. Hong Kong’s connective tissue shows here with footbridges, alleys, MTR exits, and minibus bays. Everything is within reach of everything else.

I took a small detour into Tin Hau Temple, where fortune sticks rattle and soothsayers swap futures in quick Cantonese. Incense hangs low. Outside, the Yau Ma Tei Police Station stands as a landmark in its own right, Edwardian bones against LED skies. Then the Yau Ma Tei Theatre and the old cinema circuit, one of the few places still sheltering independent films.

The old bookshops nearby pulled me in. Local histories and pocket poetry, dog‑eared manuals and tabloids. The smell of paper and dust is something you can’t download. From there, Shanghai Street unfolds as an entire artery of kitchenware: woks, cleavers, steamers, and ladles, enough to open a Cantonese kitchen anywhere on earth.

I looped to the Yau Ma Tei Fruit Market, designated Grade II in 2009, spilling across Reclamation Street and Waterloo Road like a working museum. Drivers curse the choke points, yet vendors keep tempo regardless: pre‑dawn crates, noon shouts, midnight handcarts. It is busy because it has to be.

From there I set my sights on Langham Place, Mong Kok’s north star. It is the tallest in the cluster, a young‑at‑heart mall with an escalator that feels like a runway. It rises from wet‑market grit with a charming oddity, stitched into the street rather than sealed off from it.

Mong Kok remains the heartbeat of Hong Kong’s younger generation: sneakers, side quests, side hustles. Energy that does not ask permission.

Why walk this line? Because Nathan Road tells you if the city is thriving or tired. Today it felt alive: shops arguing for attention, traffic threading needles, people moving with intent.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 5 challenge in Sha Tin District!

Fifth entry: Sha Tin — bridges, bikes, and bright red incense

I began at The Wai, the brand‑new MTR megamall that now looms over Sha Tin’s lower skyline. Its dark, glassy exterior reads almost monastic against the pale concrete and pastel housing blocks around it. Inside, escalators rise like airport jetways, feeding commuters into an atrium of polished stone and curated calm. Step outside and the tone shifts: the whirr of bike chains, the thump of basketballs on painted courts, the midday shuffle of prams and school uniforms. Sha Tin is stitched together by overbridges and an underground cycleway; of all Hong Kong’s districts, this one seems to believe in bicycles not as novelty but as a viable spine. You feel it in the steady cadence of riders—delivery workers, retirees, teenagers—moving in parallel with buses and foot traffic.

I cut from the mall into older textures: Sun Yuet House and the cluster of public‑housing blocks carrying the patina of decades. Laundry lines bloom like flags. Sexagenarians claim the shaded benches with newspapers and quiet Cantonese. Near the estate sits a mushroom‑shaped cooked‑food kiosk—rounded canopy, scuffed counters, plastic stools that have weathered too many summers. It’s an anchor point that refuses to be displaced by glossy chains, a reminder that convenient stores do not replace community.

From there, Che Kung Temple pulls you almost magnetically. The approach is a gradual flood of red: pillars, banners, the shimmer of lacquer and gilt. On a hot day the incense is not just a smell but a texture, a visible veil that slow‑walks the crowd. The temple’s geometry—the symmetry of its courtyards, the way roofs stack like steps toward the sky—creates an engineered serenity even when it’s bustling. Stand in the shade, listen to temple gossip, and watch the collective choreography: bow, circle, wish, exhale.

Leaving the temple, I followed the Shing Mun River promenade. This is where Sha Tin takes a deep breath. The path widens, and the city’s soundscape thins to bicycle bells, soft conversation, and the occasional skate wheel clicking over a seam. The river is not dramatic, but it is steadfast, a corridor of light and motion that gives the district its sense of scale.

The promenade carries you to the Hong Kong Heritage Museum, a building with a dignified, almost scholastic presence—brick, symmetry, a retro‑inflected silhouette that feels intentional rather than nostalgic. Inside, the air cools and the pace lowers. For many, the magnet is the Jin Yong Gallery. Panels and manuscripts reconstruct entire moral universes: codes of honor, mountain hermitages, sect rivalries, the decisive flick of a sleeve. For those who grew up with these novels, it feels less like an exhibition than a return. As a teenager, I devoured wuxia here and learned the cadence of written Chinese; Jin Yong remains a favorite, a national treasure.

The museum’s wider galleries round out the day: Cantonese opera alongside pop culture—posters and costumes from classic films, music ephemera, television icons—ink paintings that fold mountains into a few strokes, and city relics that trace Hong Kong’s shift from handmade to high‑speed. It is a house of cultural memory that invites you to linger.

Why walk here? Because Sha Tin shows Hong Kong’s engineered grace: pragmatic and breathable, devotional and everyday. It is a district where modern retail sits within sight of public housing; where a temple keeps time with commuters; where a river gives you space to remember what the city is built upon. Bikes, bridges, and stories—held together in an easy loop that reveals more if you go a little slower.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 6 challenge in Tuen Mun District!

Sixth entry: Tuen Mun — wind, rails, and a Saturday court

I started on the Tuen Mun Promenade, where the autumn breeze comes in steady bands. Almost too windy, but in the best way. The air feels rinsed. Across the water, Gold Coast sits like a sun-bleached postcard, and beyond it the airport is a faint silhouette, planes sliding in and out like punctuation against the sky. The scale here is different: horizon, harbor, sky, everything given room to breathe.

At the side of the promenade, the old Kai Fat mall keeps company with the newer MTR-run Ocean Walk. Mechanical versus old: one all polished escalators and clean lines, the other a little scuffed, a little stubborn. Outside the older strip, a café spills onto the pavement under willow trees, chairs angled toward the sea, an autumn picture in slow motion. Next to it, the Light Rail glides past, Tuen Mun’s veins, steel on steel, soft motor hum, doors chirping open and shut as it threads courtyards and crossings through weekday errands and weekend drift. The Light Rail fits Tuen Mun’s zeitgeist: built for short hops, street level, threading housing estates, running on an honour-based, gate-free system. Convenience plus speed.

I climbed to the rooftop courts near Siu Hei Court. Kids everywhere: crossover dribbles, small arguments settled with rock-paper-scissors, the universal language of playground rules. It pulled me straight back. Organized sports take up most weekends now, with booked pitches, fixed rosters, fees and fixtures, but these courts taught a different rhythm: make it, take it; losers off; call the score loud so the next team hears. One point at a time, winner stays. A Saturday well spent. It still is, for the kids learning pace and space, and for anyone on the railing, letting the noise and the wind take over.

From there I drifted toward Butterfly Beach. The path slides past housing blocks and a lattice of Light Rail stops, then opens to the water again. Butterfly is more lived in than pretty: barbecue pits sending up thin blue smoke, families staking out tables with foil trays and chatter, cyclists coasting through at a considerate clip. The sand is coarse, the sea a workable gray-green, the breakwater dotted with anglers working patient lines. Freight vessels angle across the horizon, steady and indifferent, and the wind carries salt, charcoal, and something sweet from a cooler nearby. It’s not a postcard beach; it’s a holiday beach, functional and communal, good for an unhurried hour and a slow walk home.

Why walk here? Because Tuen Mun runs on useful contrasts: sea wind and rail glide, an old mall holding ground beside a new one, improvised games alongside scheduled leagues. It moves at a human clip, with wide views and small rituals—dribbles, charcoal smoke—stitched along a shoreline you can follow without checking a map. And there’s a quiet social contract at work in the Light Rail’s honour-based, gate-free system and zonal tickets: a small act of trust that fits the district’s everyday rhythm.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 7 challenge in North District!

North District — edge, river, in-between

North District read like a hinge. Small industry still lived here—metal workshops, packaging sheds, cold stores—tucked beside low‑rise village houses and tiled clan halls. Close to China, but the aura was unmistakably Hong Kong: green metal shutters half open, plastic stools under awnings, a cha chaan teng named after a Stephen Chow character that knew your order before you sat. Even the taxis said it out loud. They were green here—far from the usual red—and the color echoed the place itself: layered greens of hills, banyans, and the lush margins around heritage sites.

I started at the Beas River Jockey Club for a wedding. The mood shifted: clipped lawns that measured colonial geometry in the alignments. It felt like the most British corner of the district, a cool line of water and grass that calmed the edges. The whole place sat in a gap, almost slotted between a newer Hong Kong and China across the fence—border lights on one side, village dogs on the other, freight horns somewhere in between.

The trail’s history sat in the stones. Lung Yeuk Tau was Tang clan heartland—settlements from late Yuan and Ming through Qing, fortified against raids and aligned by feng shui with hills at the back and water at the feet. Walled villages kept gates and watchtowers; ancestral halls anchored lineage and ritual. Restorations came in waves—first necessity, later grants—so original gray brick sat beside careful repairs: defense, devotion, daily order.

Context made it sing. Beyond a gatehouse, a small construction site hummed. Over the next wall, new low‑rise blocks stood like a second horizon, glass and beige panels catching stray sun. The contrast worked—not heritage in a bubble, but heritage in a neighborhood. A villager swept; a courier scanned a parcel; a school group counted off in twos. A shrine faced a car park. A temple looked across to a slope of new trees. Time didn’t cancel; it layered.

On the way back I detoured through Luen Wo Market. Post‑war market‑town bones remained—arcades, signboards, stalls spilling greens, the clatter of cleavers. Once the commercial heart for villages around Fanling, its rhythm lingered: hawkers calling prices, a herbalist measuring roots on a brass scale. You could taste the district in a bowl of noodles and read its memory in shutter patina.

Needing a break, I drifted to Green Code Plaza. Local malls showed how people lived. This one was practical, not precious. A supermarket pushed crates of choy sum and mandarins to the threshold. A seamstress kept a corner by the escalator, tape like a necklace, school uniforms waiting for Monday.

You could read a neighborhood by how long people lingered. Here they lingered just enough. Not a destination mall, not a transit blur, but a ledger of needs met and errands crossed. On Sundays, helpers gathered in shaded corners, phones on speaker, harmonies rising over picnic tarps—laughter, songs from home—an unmissable Hong Kong chorus. Overhead, the AC hum matched the minibus rank outside.

Before I closed, I cut across to North District Park. A pond with fat carp nosing the surface, red footbridges, willows throwing broad shade. Elderly couples walked laps; groups shifted like a slow tide. On the courts, teenagers played volleyball, cheering points and misses alike—high‑fives, mock groans, someone filming on a phone. It felt Gen Alpha in the best way: open, unserious, claiming new‑town space as their own. The park gathered the district’s mix in one frame: tower blocks above tree lines, a soccer pitch buzzing with shouts, a pavilion where cards slapped on stone tables and a radio played the horse races every Sunday, echoing the jockey club nearby. Two worlds sharing the same longitude. Wind through trees, cut grass, a brief calm before errands resumed.

Stepping back out, the border returned in small ways: a sweep of hills that looked north, a line of lights that said there was a fence even when you couldn’t see it. North District held its balance—industry next to clan halls, heritage under high‑rises, a colonial river cutting a quiet line while trucks grumbled past. If you wanted to understand it, you walked the trail, then the market, then the mall, and ended in the park.

Why walk here: to watch history and the daily list talk to each other, and in the kids’ volleyball joy hear a future Hong Kong, already practicing.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 8 challenge in Tsuen Wan District!

Tsuen Wan — red line, river wind, remake

Before the MTR became what it is today, the red Tsuen Wan Line was the through line that connected the city’s everyday life. It stitched Kowloon to Hong Kong Island, carried factory shifts and school runs, and made Tsuen Wan a name everyone knew. Tsuen Wan used to be as far as I’d ride on that line, the terminus that taught you what “end of the line” felt like. Now it anchors red at one end while Central holds the other: two bookends on a line that borrowed Tsuen Wan’s name. Unmistakable beginning and end, and a reminder of how this district helped hold the city together.

December crept in early. Christmas decor bloomed over a town where OP’s name carries a light, subtly romantic lilt, and it wore the tinsel with ease. OP Mall, standing apart from the overpass web, threw up trees and mirror baubles that caught the trampling crowds. On the new harbourfront, people arrived in waves: strollers, cyclists, teenagers in matching hoodies. A new community pressed up against the water, and in November the first proper breeze finally moved through, salt, steel, and winter’s edge.

Sound tracked it all. Each era carried its own channel: uncles pedaling to 80s Cantopop, teens looping K‑pop and EDM, joggers locked into podcasts. Threads that shouldn’t align somehow do, a unique symphony stitched across the promenade.

I walked from Castle Peak Road in Tsuen Wan and cut to Lai Shun Road, slid past the Tsuen Wan West Sports Centre, crossed into Ho Shing Garden. The legs of the elevated road loomed over benches where people talked and dozed; beneath them, graffiti that feels uniquely Tsuen Wan, easy to miss unless you’re on foot.

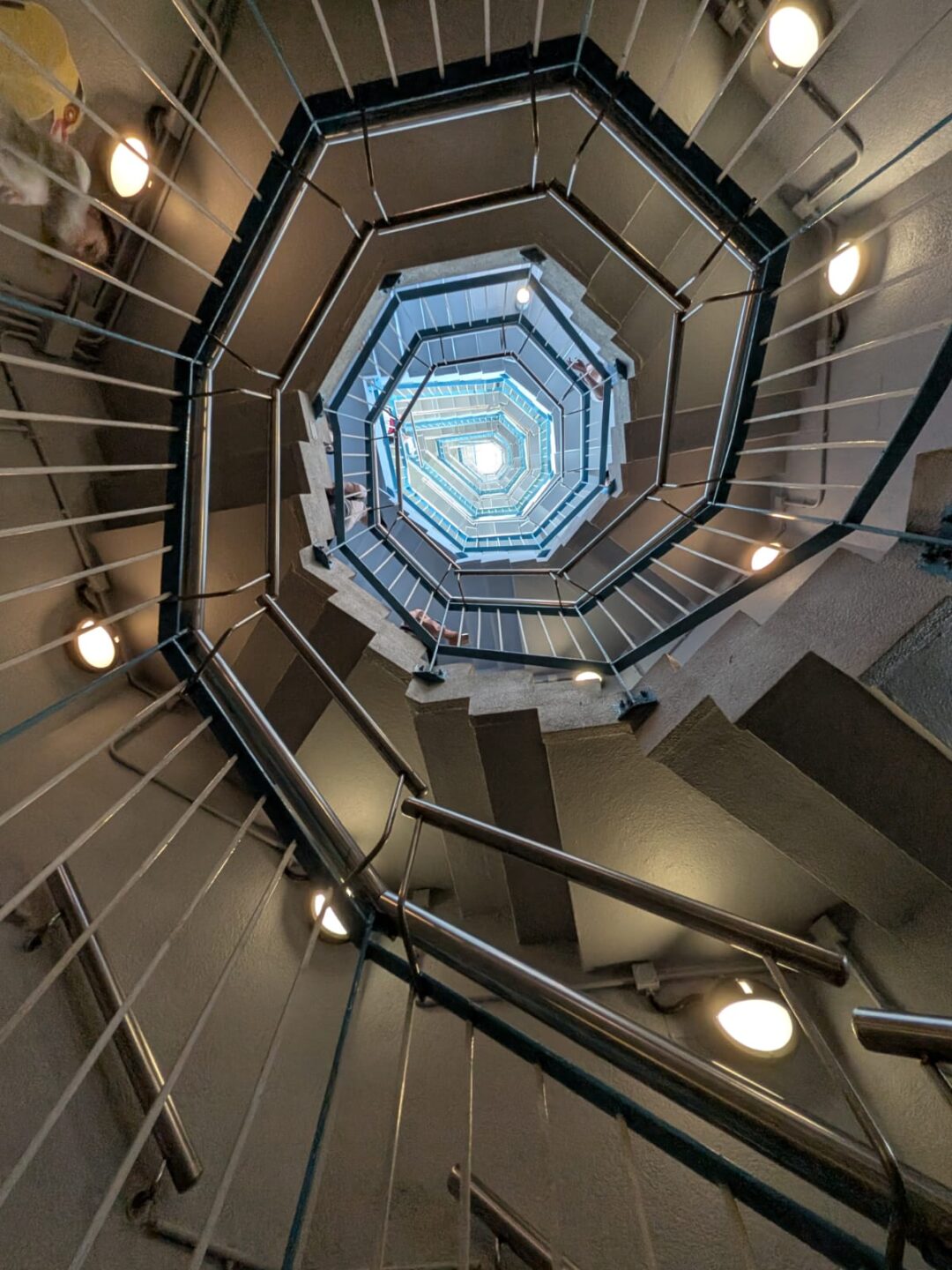

I followed the weave to The Mills. If Lai Chi Kok has D2 Place, Tsuen Wan has The Mills: cotton memory spun into a contemporary hub. The restoration kept the mill’s bones—concrete, spans of light, stairwells that feel honest—and layered in galleries, cafés, maker floors, and that photogenic interior. Outside, Vhils’s carved portrait, Nameless Heroes, sometimes called “factory girl,” faces the street, a tribute to the workers who powered Hong Kong’s industrial golden age. It reminds you what the city used to be; step inside and the interior hints at what it will be. Even the police station here looks freshly minted: glass, angles, a modernist calm that matches the remake.

The overpass network took me back into the heavy city: Citywalk I & II and the vast Nina complex, Chinachem’s estate of glass and air‑conditioning, stitched together at second‑floor level so you can walk a kilometer without touching ground. Bridges cross Tai Ho Road like articulated arms; you step from one microclimate to another, from bakery warmth to department‑store chill. This is where the late Nina Wang’s hand still shows. She steered Chinachem through the district’s pivot from factories to services, planted the flag with Nina Tower, and set the template for an integrated core: offices above, hotel and mall below, bridges binding it to the civic grid. The complex turned a tangle of roads into a center of gravity, proof that Tsuen Wan could be a destination, not just a terminus.

People say the heart of Tsuen Wan is Nina, and you feel why. The skyline spikes at Nina Tower’s twin forms, the north tower rising as the district’s tallest, a literal North Star for the streets below. From there the flow is constant: overpass to plaza to market and back, commerce, lunch breaks, violin practice bleeding from a rehearsal room, and the rumble of trolleys under the flyovers.

Among all the districts, Tsuen Wan has it all, the most coherent ecosystem in the city, a self‑contained loop that works at every level. I ended where I began, in red. A place that was once my farthest station is now a city of its own I walk for the weave: harbour wind, bridge‑light, cotton turned culture, and the music of a crowd learning its own rhythm.

Why walk here: for harbour wind and bridge‑light, cotton turned culture at The Mills, and the crowd’s mixed‑era soundtrack under Nina Tower’s skyline.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 9 challenge in Kowloon City District!

Kowloon City — names, memory, flight path

Before I turned south, I began on Prince Edward East under the quiet gaze of St. Teresa’s Hospital, then crossed to the church that shares its name. My primary school is gone now, doors shut and corridors emptied, but the nave still holds its calm: terrazzo floors, soft light, a parish that keeps time by bells. From there I drifted to Maryknoll, my sister’s alma mater, another classic face in brick and lime, a place that wore discipline and gentleness in equal measure.

I let the route slip south without pausing long in Kowloon City proper, the old market town that once sat under a flight path and the shadow of a different sovereignty. Ahead, the infamous becomes improbable: Kowloon Walled City Park, a landscaped calm where the world’s most famous density once stacked families and trades into an anvil of light and wire. It is perhaps the old Hong Kong most outsiders know: narrow alleys, neon dentists, a city inside a city. Now the park is a study in memory, with gate names and yamen stones pinning the stories in place.

Around it, Kowloon City remains its own country. Thai groceries spill lemongrass and kaffir lime onto the pavement; dessert shops, curry houses, and mortar‑and‑pestle som tam give the air a different rhythm. The fabric mixes old tong lau with small high‑rises, balconies hung with laundry above bakeries and cha chaan teng. It’s an honest contrast: heritage and upgrade sharing the same block.

Song Wong Toi station has pulled the area nearer, a new seam in the map that puts markets, temples, and noodle streets one transfer away. The name remembers the boulder once revered, shifted and memorialized, history adjusting to engineering and back again.

Not far off, Kai Tak explains why the world learned to say “Hong Kong” with a grin. The old airport taught pilots precision and residents patience; the checkerboard turn was a citywide sport. Now the runway is a spine for another future: a harbourfront grid with a cruise terminal, promenades, and a world‑class sports complex rising.

It’s a hub on the site of The Sports Park’s bowl, indoor arena, and community pitches promise noise on weekends and light on weeknights, a new commons where roar replaces jet whine. The old apron has been parceled into new housing, offices and megamalls, with streets named for sky and sea, and the riverside walk lets you trace the line where planes once skimmed laundry poles. It’s a hub on the site of an airfield that predates colonial days, proof that arrival keeps changing shape—first by air, now by foot, bike, and a skyline learning how to look forward.

I looped back to St. Teresa’s where it began. Hospitals and churches, schools and markets, parkland layered over legend, an airport reborn as a district. Among Hong Kong’s neighborhoods, Kowloon City holds a full syllabus: past, present, and a flight plan for what comes next.

Why walk here: for church bells and school gates, the hush of Kowloon Tong and the bustle of Kowloon City, Thai flavours along Nga Tsin Wai Road, the memory architecture of the Walled City Park, and Kai Tak’s wide‑open future under a sky once cut by wings.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 10 challenge in Wan Chai District!

Wan Chai — frame, ferry wind, fast lane

I began at Golden Bauhinia, that ceremonial bloom facing the harbour like a perpetual ribbon‑cutting. From there I slipped onto the promenade, the boardwalk that turns office glass into sky. Past the piers, Victoria Harbour opened clean and blue; Kowloon stood crisp across the water, every ridge and rooftop accounted for. From the pier rooftop, Hong Kong fits into a single frame: ferries threading the channel, the invisible cranes at Kai Tak, the mid‑levels stacked behind Central, and Wan Chai’s own glass learning to reflect it all.

Wan Chai connects the picture—Kowloon on one side, Hong Kong Island on the other—and the promenade is the stitch that holds them together. There’s a pier here now that ferries you straight to the Kowloon side, a small hop that makes the frame feel even tighter. Nearby an odd exhibit sits on the waterfront: two retired “fly‑head” train carriages parked by the sea, a railway that no longer runs catching its breath at the edge of the harbour. It’s strange and somehow right—Harbour Station, they call it—steel on sleepers meeting salt and swell, the city’s twin instincts of motion and mooring fused into one view.

I followed the curve toward Causeway Bay Typhoon Shelter, where the yacht club sits inside a pocket of still water. Old sampans and polished masts used to share the same mirror; the skyline reads like a catalogue of eras, neon ghosts under LED skin. It’s Hong Kong’s favorite contradiction: craft and capital, diesel and gin, the old and the new tied to the same cleat. The breakwater holds the swell at bay—its own wall against the harbour’s restlessness.

I ducked through the underpass to the World Trade Centre, then floated with the tide past SOGO and Times Square. So many names borrowed from elsewhere—places that promised a world and delivered a version of it in escalators and atriums. Causeway Bay showed the bustle in full: street crossings choreographed by screens, snack lines curling around corners, the city’s challenges written in rent signs and tired faces.

The luxury shopfronts at Matheson Street’s junction are gone now; sheets of paper in the windows, a brief pause in a district that hates silence. It has always been an inlet for new waves—mainlanders arriving on long weekends, their footprints still faintly visible in the inventory: COVID‑era mask stalls turned souvenir carts, phone‑case pyramids and luggage shops, then the pivot to athleisure, skincare, and bubble‑tea chains. Causeway Bay absorbs each season’s demand and moves on, an economy that breathes in surges. Through it all the tram keeps its own tempo, bells blinking through traffic as it glides along Hennessy and Yee Wo—timbered patience against the hurry of footsteps, unbothered by screens and sales.

I cut inland to the Hong Kong Football Association ground and leaned on the rail to watch an amateur match—almost like being somewhere else. Expats and locals traded commentary in two languages, the linesman’s flag bright against the turf, the city briefly agreeing on rules, time, and a scoreline. From there I carried on along Sports Road, the Happy Valley Racecourse opening in green relief. On a Sunday the infield turns into a commons: joggers and frisbee arcs, prams and five‑a‑side, sun scratching at shoulders while towers look on like grandstands of glass.

I walked into Happy Valley proper, where streets tuck in against the track—Blue Pool, Village, Sing Woo—blocks that feel like a neighborhood rather than a system. Cafés under awnings, dogs dragging owners toward parks, stairwells that smell of last night’s dinner. The city takes a breath here before the next sprint.

Why walk here: for the harbour in one frame from the pier roof, a ferry hop straight to Kowloon, the still water and breakwater wall of the typhoon shelter against a restless skyline, the borrowed names and crowded crossings of Causeway Bay with a tram keeping time, a match at the FA ground, and the long green pause of Happy Valley under Sunday sun.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 11 challenge in Yuen Long District!

Yuen Long — pride, plains, perspective

Yuen Long carries itself with a particular pride, Yuen Long 人, that no other district quite has. Hong Kong likes to boast about density, a small city that somehow enlarges your view; Yuen Long proves it. On a map it’s far, a broad swath of New Territories, but on foot it tightens into scenes that feel both rooted and immense.

I came in past secondary schools with banners listing university offers, names printed in Chinese, pride pinned right to the railings. It feels organic here, not a billboard for outsiders but a bulletin for the neighbourhood. It is proof that study and staying power still matter. Not just what I do, but what I believe: education as the great equaliser, still worth my faith.

Yuen Long Park rises like a resort: palms, red Spanish brick, and a breeze that edits the day. I climbed the Aviary Pagoda, each level opening a wider circle until the plain and its mountain ring settled into one view. For a moment it didn’t feel like “Hong Kong” as the postcards promise; it felt like a whole territory in a single frame: ridgelines stepping off toward Tai Lam, rooftops threading into market streets, light‑rail bells carrying across the trees.

On the bird tower, 「欲窮千里目,更上一層樓」. I don’t need the Shanxi tower it was written for to feel it; here each step widens Yuen Long by a breath, the ridges sharper, the wind farther, the heart eased open. Shanxi lingers in the phrase, 登鸛雀樓 in the bones of the words, yet the couplet lands just the same. Every 「一層樓」 carries the view a step farther. Serenity holds, then the sightline snags on a hillside of large tombstones, ancestry interrupting idyll, reminding me how the living and the long‑gone share this basin. It points to all of Yuen Long, the mountain range astonishing in its sweep; there’s a reason this is one of the city’s largest districts.

It points to all of Yuen Long, the mountain range astonishing in its sweep; there’s a reason this is one of the city’s largest districts.

Down from the tower, Yuen Long Theatre gathers the district’s stages. Inside: student work, inked modern griefs and clever pastiches of Cantonese opera, young hands playing with old forms. Outside, the Jockey Club sports grounds thrum, and the spaceship curve of the public library anchors the block, stitching a Yuen Long picture of culture, sweat, and study. The theatre is a regular home for Cantonese opera. An uncle hums an 80s tune at the door, a prelude and a lineage at once, and I’m reminded I’m well outside any set “centre.” Yuen Long stands steady in some ways, yet moves at a measured pace. I can see it.

On the pavements the air feels wider. There are Girl Scouts selling charity flags, so it must be Saturday. There are fewer chain façades, fewer For Lease signs; shops look used rather than curated. You learn quickly that charm doesn’t require sameness. An old photo studio has held its corner through format changes and phone cameras. Malls with names like Happy Plaza don’t need hyperbole inside to be Yuen Long; the name is enough. Wing Wah’s wife cakes complete the town’s centre of gravity.

Castle Peak Road and Yuen Long Main Road act like a local Nathan Road, busier, closer to the ground, riddled with local shops and market fronts, and the light rail gliding through like a metronome for the street. Turn a corner and you find Shing Yip Street, where butcher blocks thud and pork is still a place‑specific errand. Squares open where small stores cluster, each with its own radius of regulars. Step into Yuen Long Plaza and the familiar chains reappear. You’re reminded how the city standardises; the moment you step back out, the district’s own tempo returns.

I carried on to Ping Shan. Here the Tang clan wrote education into brick: study halls, ancestral halls, and a street‑long timeline of settlement.

Shut Hing Study Hall is now lived in, its narrow corridor strung with everyday utilities and washing, scholarship layered with life. In a shaded pond an old turtle keeps unhurried time, a hundred‑year heartbeat in a place that has seen examinations rise and fall. We still borrow the term 「狀元」 when we praise achievement; the Tang lineage shows why.

The Ping Shan Tang Clan Gallery, once a police station, now curates this story: salt fields to market town, clan villages to new town, a reminder that Hong Kong’s best conservation often lies in reuse rather than glass cases.

By the time I finished, my feet were blistered and my heart was full. Yuen Long is big enough to make me feel small, yet close‑knit enough to make me feel seen. It puts Hong Kong under one frame: palm shade and red brick, study banners and butcher blocks, opera arias and light‑rail bells, and lets the picture breathe.

Why walk here: a small‑vast district where pagoda tiers sip the wind, ridgelines comb the light, pork streets drum like heartbeats, opera tints the air, and study halls breathe—brick warm with memory, rooms bright with day.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 12 challenge in Wong Tai Sin District!

Wong Tai Sin — wishes, walkways, witnesses

I started at Lok Fu, the most modern stop. The mall had its Link REIT shine, glassy and efficient. Nearby, Morse Park unspooled like a maze, an amateur sports heaven; if you could tell Parks 1, 2, 3, and 4 apart without a sign, you had a navigator’s gift.

From there I drifted to Diamond Hill, toward Hollywood Plaza. Outside Chi Lin Nunnery and Nan Lian Garden the city turned curated, so composed I thought I’d stepped into Japan: timber halls, raked gravel, water slipping under bridges, the most scenic pocket in Hong Kong.

In the frame it was almost comic: the zen hush of cypress and tiled eaves in the foreground, and behind them the big “Hollywood” signage beaming from another universe, a quiet garden photobombed by showbiz.

On to Tsz Wan Shan, past hillside Buddha temples and estates that wore their years openly, laundry lines mapping wind, stairwells keeping the memory of school bags and market runs.

At Wong Tai Sin Temple by night, the market outside remixed the air. Incense gave way to the dry seafood smell—squid, scallop, abalone—and the soft music of coins and small notes. Between the temple and the old estates, pockets of colorful temporary housing stitched the gaps; seams showed, the fabric held.

Public housing gathered like a constellation. “Wong Tai Sin” meant wishes, and I felt it in the courtyards: the hope that kids playing football under block lights would grow into their own futures. Gentrification hummed at the edges, new cafés under old walkways, yet stairwells still carried last night’s gossip and this morning’s steam.

Alongside all this, Lung Cheung Highway skimmed past, a fast ribbon that let you miss the whole tapestry.

I followed the line to Choi Hung. Even the MTR hinted at abundance, three parallel tracks like a chord. The name said rainbow, and the platforms echoed it.

Ping Shek Estate reared up and made me small. I stood in the well until my hands shook, a perfect rectangle of sky, walls lifting in red, green, blue. The atrium was a lens that swallowed me, a geometry of humility.

Final stop, Choi Hung Estate. The basketball court was the city’s postcard, but at night it was better: the backboard chalked with scuffs, the court dim, a ball on concrete, a shout, a laugh. Around it, the surrounding blocks glowed like a Tetris board, lit squares sliding into place, level by level, an orderly shimmer against the dark. Every light signaled a household, a new story waiting to be told about Hong Kong. This was as local as it gets. I loved the everydayness of it. Hong Kong is more than a harbor; it’s the people who make up the fabric of the place.

Why walk here: wishes in the estates, a temple breathing next to a market, gardens built like poems, parks made for play, rainbows cast in concrete—places that shrink you just enough to feel seen. The famous sights don’t tell the whole story. These ordinary blocks fill in what’s left unsaid, giving the city balance and context. Without them, Hong Kong is a sketch without detail.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 13 challenge in Kwun Tong District!

Kwun Tong — smoke, shoreline, second chances

I started at Kwun Tong Hoi Bun Park. After Tai Po, the city felt muted: fewer easy smiles, a hush along the water. I was walking for charity, holding a small thread of hope. That was enough to begin.

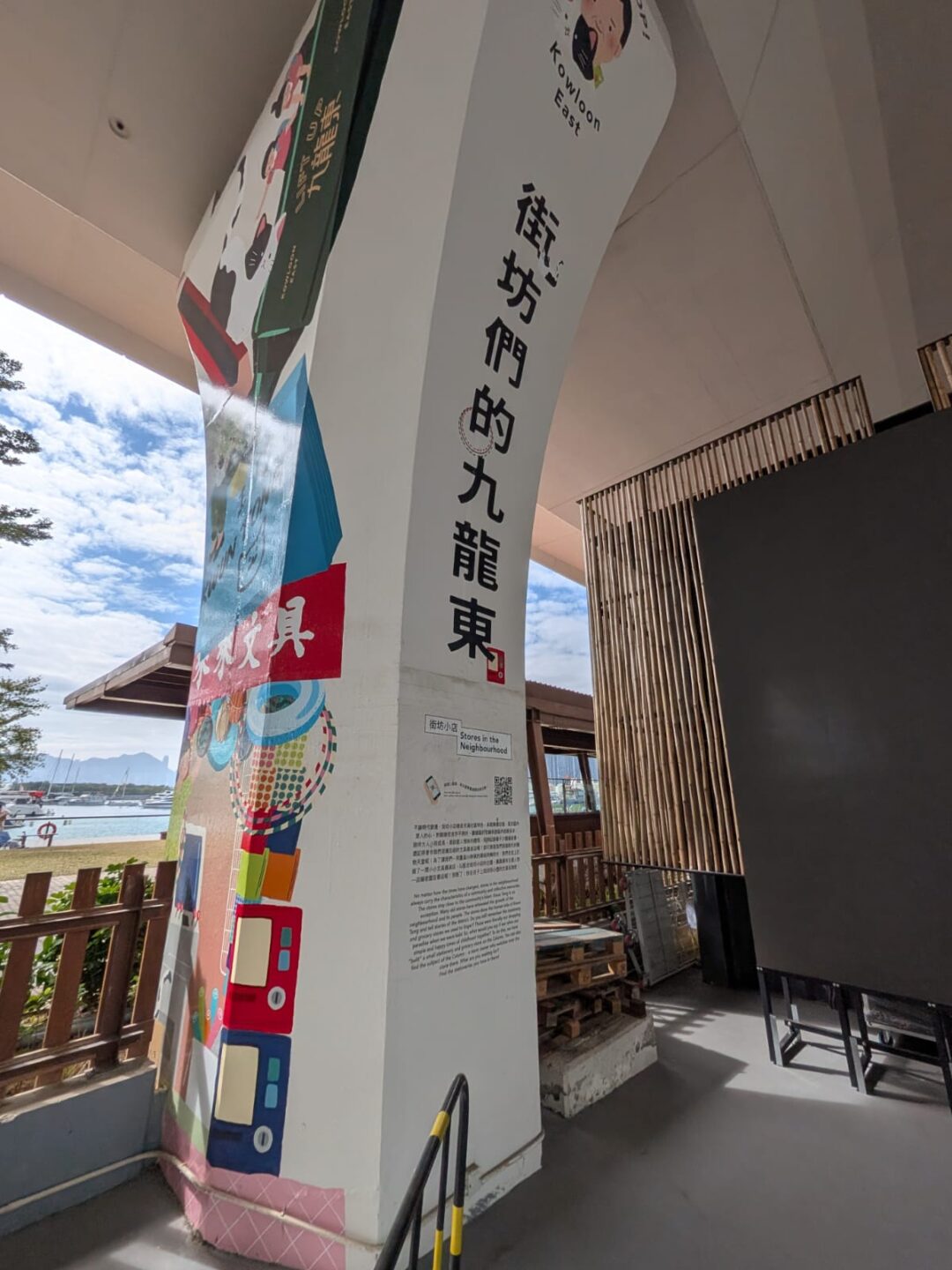

Kai Tak hovered in the backdrop, a habit of arrivals. Under the overpass, graffiti mapped Kowloon East: factory floors turned office cores, dock grit traded for cafés. Hoi Bun’s edges had the soft shine of gentrification, planters and joggers, good dogs on good leashes. MegaBox loomed inland, Kowloon-sized and unapologetic. Kowloon Bay Park tugged at memory, football on scuffed grass, bad bounces teaching good timing.

Kwun Tong carries a long apprenticeship in making things. In the 1950s and 60s it powered Hong Kong’s industrial climb in textiles, plastics, electronics. Open-front workshops, lunch pails on curbs, sirens marking shifts. When the factories moved north, the district did not quit. It repurposed. Mills to studios, godowns to offices, old stairwells still warm with steam and gossip. That is Kowloon East’s trick: rise, adapt, rise again.

We all felt what happened in Tai Po, even from here. No need to name every detail to know the weight. The city’s reflex was clear. Donations poured in from every corner, kitchens stayed open past midnight, schools and community centres unlocked their halls, shops turned into supply depots, strangers lined up with water, chargers, hot meals. Tai Po was the epicenter, but Hong Kong moved as one. We live by district, we act like family. Flags across the city hung at half-mast, an outward hush on the skyline. Out of the ashes, we did not just rise, we reached for each other.

I traced the Tsui Ping River and cut past the Composite Centre beside the Christian Family Service Centre, everyday nodes of care in an industrial belt. Even here there is choreography: errands, eldercare, deliveries, a local mesh that catches you when something tears. The open-track blocks of Kwun Tong still hum, repairs, forklifts, daycare runs, a dozen small labors that keep the city stitched.

At Kwun Tong Park, kids chased light across the playground. Parents talked in low voices. A ball thumped concrete. Hope is not loud; it is a routine that refuses to stop. The city is a kiln. We enter as clay, and time, plus heat we did not ask for, hardens us into something that holds. Ash to glaze, smoke to shoreline.

Why walk here: to watch a district practice resilience in plain sight. To see how Kowloon East folds its factory past into a livable present. To remember that good things take time, like healing, like neighborhoods learning new forms without losing old strengths. Kwun Tong keeps getting up. So do we.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 14 challenge in Hong Kong East District!

Hong Kong East — red and white, work and night

Taikoo starts in a flash of red and white. Mall, MTR, residences, the names run together so smoothly it is hard to know where one begins. The trace feels like it could run forever. Glass and stone, escalators like rivers, a district learning to move as one piece. Long before lift lobbies and lunch crowds, this was Swire ground: first sugar, then the Taikoo Dockyard hammering hulls into the channel. When the dock whistles fell silent in the late 1970s, the cranes learned a new grammar. Taikoo Shing rose on reclaimed land as one of the city’s earliest large private estates, and Quarry Bay kept the quarry’s old name even as rail stitched industry to offices and homes.

I walk east to Shau Kei Wan. Tai On Building wakes after dark. Tables spill out, grills hiss, neon hums. Here it stops feeling like an extension of Taikoo and becomes itself. Tai On is a landmark on its own, proof you do not need Lan Kwai Fong to have a nightlife. You need regulars, hawkers, and room for talk.

History runs close to the curb here too. Shau Kei Wan began as a fishing village on a scallop shaped bay, boat yards and temples serving Hakka and Hoklo communities. After the war, waves of migrants filled resettlement blocks, markets thickened, and trams and the MTR pulled the old waterfront into the city’s bloodstream.

The line tapers at the terminus. Chai Wan carries an old slope of graves and an industrial edge, but a youth centre dances concrete into motion next door and lends the place a pulse. Sprinkle in teenagers from old estates and backpackers from the youth hostel and it reads less like an ending and more like an opening, a last stop with plans.

Shau Kei Wan’s Indonesia satay stalls tell a quieter story of Hong Kong. Immigrants found footing, traded spices and language until the flavours turned local. Along Aldrich Bay the air softens, water takes the hard out of the grid, and the walk pours into the curve of the Monster Building.

The Monster Building is a contradiction that works. It draws tourists like a lens cap removed, a canyon of flats revealing the scale we usually sense but do not see. There is a tint of sadness in the green construction mesh, a reminder of the recent tragedy. Around it, the real neighbourhood is stitched by small shops. Seamstresses and locksmiths, soy milk and key cuts, the everyday that keeps spectacle honest.

Back toward One Island East, Taikoo reprises the blend. Offices ringed by homes, helpers gathering on Sundays with food and laughter, a plaza turning into a living room. Work and residential fold into each other until the calendar makes more sense than the map.

Why walk here: Because Hong Kong East refuses to end. Red and white becomes neon and steam. Cemeteries sit beside studios. Hostels beside housing estates. Immigrants beside regulars who arrived yesterday and stayed. It is a coast that keeps composing itself, mall into market, tower into tenement, night into morning. The line you follow does not stop. It changes key. Youth places are sprinkled across Hong Kong East: centres, courts, corners to dance or drum, small lights that keep the beat between stops. And in that key there is a quiet hope: our steady effort to return to normal, to stitch days back together until routine feels like promise again.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 15 challenge in Hong Kong South District!

Hong Kong South — sea light, slow air

Stanley began in a wash of blue and hush. Long Tai Court showed the first square of color, an estate tucked low by the water, laundry lifting in the salt. The pace dropped a gear the moment I turned the corner. Sea on the edge of vision, hills trimming the wind, shopfronts speaking under their breath. Calm wasn’t empty; it was measured. Older names rode the breeze: Chek Chue before “Stanley,” Tin Hau keeping watch, reminders that storms and junks once set the calendar here.

Murray House once drew weekend crowds like a beacon. Now the arches kept more sky than footsteps, a handsome shell with a memory. It was moved stone by stone from Central, nineteenth‑century granite learning a new address. Down the slope, Ma Hang Park did steadier work: signboards, lookouts, the long view of pirates, markets, and garrisons folding a village into a town.

At Stanley Corner the yellow block lifted the junction like a flag, one of those waypoints that doesn’t need an address. The road leaned into the slope. Quiet traveled farther than engines. Cafés traded in shade, stray dogs rotated benches, the old police station by the water looked on like a retired sergeant taking attendance.

I slid past the market and bus bays, crossed the little square at St. Stephen’s, and the volume fell away. Prison walls, the wartime cemetery, names in rows under still trees. In 1941 this hillside was a last stand. Classrooms carried the battle, and the cemetery kept its ledger. It felt less like Hong Kong and more like a held breath inside it.

Repulse Bay curved ahead like a practiced line. Holiday bright, clean lights along the arcade, garlands in tidy geometry, a wedding party under the white arches rehearsing applause. Once this beach shared space with a rifle range. Money and peace redrew the shoreline and softened it into apartments and weekends. Lily Tower looked on while a market dialed up the season: paper cups of spice, brown paper parcels, small gifts that felt larger in the hand.

Repulse Bay Beach is the silhouette everyone carries. Behind the glass, the richest homes closed their curtains early, evening before evening. Across the water in Choi Hung and kindred blocks, windows yawned open to catch light. The contrast didn’t scold; it clarified. Privacy and show, exclusivity and everyday, two notes that still make a single city. Here the voices tilted English, expat cadence layered over Cantonese, and I felt that familiar foreignness that sometimes passes for belonging.

The promenade ran easy. Deep Water Bay slipped by, Middle Island sat like punctuation. A breeze held the walk together. Kids counted buoys, runners slid around prams, old men angled lines for luck. Ocean Park hung on the hillside, cable cars penciled in, a 1977 promise that leisure could climb.

Between main curves, small details did the talking. A temple roof tipped the corner into a story. A bus stop offered a timetable nobody believed and everybody used. Villas looked outward and inward at once. A guard’s booth held a thermos and a patient plant that kept the same hours. Dusk did what it does, one light, then another, until the water borrowed the city and brought it closer.

I finished at Repulse Bay Plaza. Another wedding unwound in the square, one more turn, one more clap, one kiss on cue. It was a good day. People were easy with one another. The weight loosened, and the apology we carry here thinned in the salt.

Why walk here. Because the south coast lets the sea keep time. Arches and markets. Cemeteries within earshot of ice buckets. Curtains drawn tight and windows thrown wide. English riding the air, Cantonese threading through it. Coastlines shifted with forts and hotels and still learned a softer weekend grammar. This edge of the island doesn’t end so much as change register, and in that register lives a quiet hope: to keep walking the easy edges, collecting light and names, until the next season opens like a door.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 16 challenge in Sai Kung District!

Sai Kung — a cooler breath, a softer register

I arrived where the ocean pretends to be a mall. Glass caught tide light and the boards hummed under sneakers and paws. Bicycles chimed like small bells. Dogs, so many dogs, noses to the wind, tails spelling easy grammar. Low-rise blocks kept their heads down. Density thinned to a hush you could walk inside. Space wasn’t empty; it was spare, like a blank margin inviting a note.

I passed the IVE and came to the anchor of the district, the Hong Kong Design Institute. Concrete and glass held clean chords, a school staging its own future. Studios stayed lit late. Foam and wire models crowded tables. Sketchbooks flickered like shoals. Creativity stood in daylight without apology. These shores once worked in salt and fish and families tied to tides. The hands remain; only the materials and lamps have changed.

I followed the water’s edge. The boardwalk became a path, and the path became a park. Tseung Kwan O South opened in order: TKO South Park first, then the Shoreline. A steady breeze stitched the segments into one breath. Prams slid past pedals. Leashes crossed and uncrossed. Runners counted lamps like beads. Across the basin, Metro Town rose in tidy strata, glass blinking domestic constellations. The air cooled by a degree as the sea found its voice.

I stepped onto the Cross Bay Bridge. The horizon learned to curve. The arch looped like infinity and kept its promise by carrying me across. It was shaped to mimic infinity, a gentle claim that cities can keep going without coming apart, that return is part of progress. Underfoot, the cables hummed a note I felt more than heard. From the span, I could look far. LOHAS Park lay to one side and Tiu Keng Leng to the other, with Tseung Kwan O gathered like fingers into a palm. The cemetery terraced itself into the view, a reminder that a city is a circuit where beginnings and endings share a railing.

On the far skyline I could make out the new Chinese hospital, pale and precise, seen only from a distance, a quiet assurance.

Back on the ground, the planning felt composed without fuss. Courtyards held a conversation. Benches met the shade. Ramps appeared where they were needed. Corners forgave a stroller, a scooter, or an old knee. The place felt enclosed but not gated, like a village folded into a town where most things can be carried by hand. The bridge made the logic visible, linking LOHAS Park, Tiu Keng Leng, and the waterfront in one gesture. You can start anywhere, circle the neighborhoods, touch the lip of water, and come back to the same square without breaking the spell.

Evening arrived one light at a time. The bridge drew a luminous loop. The park exhaled. Dogs made last circuits with satisfied gravity. Somewhere a design student pinned a final to foam. Somewhere a family lifted a bowl to steam. The apology we carry in denser districts loosened here, thinned by salt and by lines of things built to be used well.

I ended where the town still breathes in lists and prices: Sai Kung Market, last stop. This is the resort feel I meant, not a gated resort but the ease of the Town Centre. Marina chatter and seafood glow set the pace. A small-harbour breeze cooled the skin and the tempo. Fish lay on ice, greens sat in baskets, and the air rang with scales, hose water, and small bargains. Boats nodded at their moorings like punctuation at the end of the day. Begin and end in one loop, the living and the gone within earshot, and the cooler breeze makes the whole place feel like a weekend you haven’t quite deserved but get to keep.

Why walk here. I’ve walked 16 of Hong Kong’s 18 districts, and this one feels less like consistency and more like a mosaic: shore and bridge, institute and market, prams and pedals and pawprints fitted edge to edge. Sai Kung lets the sea set the metronome, keeps the buildings low and the sky wide, and proves that bikes, pets, and prams can share one sentence without tripping. The arch returns you home, the breeze keeps its promise, and the loop holds beginnings and endings within earshot.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 17 challenge in Island District!

Island District — an island hinge, a city in crosswind

I arrived where the Citygate mall is an ecosystem and the outlet is a magnet, especially on the first day of 2026. Glass stacked on glass, escalators flowing like streams, luggage wheels ticking a tourist tempo. It was New Year crowded, the kind of celebratory press that says Hong Kong is back in 2026. Announcements braided Cantonese and Mandarin and English. Perfume drifted in a bright ribbon between sports shoes and suitcases.

I stepped out toward Tung Ma House and the familiar face of subsidized housing. The blocks wear the same measurements citywide, but here the pace loosens a notch and the air tastes rinsed. The mountain stands close behind like a steadying hand. Density thins enough for breath to have weight. Laundry flutters against green slopes, a local postcard tacked to concrete.

Yat Tung Estate spread on wider streets, a grid that lets prams and trolleys take their time. Corner shops blinked, aunties compared greens at a pace that felt pre-rush, and the chatter rounded its vowels again. The place felt local, less hurried, more neighborly, like the city remembering itself between errands.

Back near the center, the poems appeared. Along the mall and the estate, stanzas trimmed into panels and walls, a quiet margin for looking up. They were different voices and yet part of one link, an overlay of small histories on standard-issue forms, proof that repetition can still host a thousand variations.

The market staged a memory of old Kowloon City. Red lamps and close counters, fish waking the air, but with exits widened and edges clean. It made a theatre of appetite and barter, a remake that knew its source material and kept the cadence even as it softened the corners.

I cut across to Tung Chung Fort, quiet stone folded into the middle of modern blocks. Cannons rested in green, trees anchored the sky, and the wall kept a line through time. History here doesn’t declaim; it sits and watches the elevator doors open and close, a garrison turned garden, reminding you that the present is a recent tenant. Built in 1832 during the Qing dynasty to guard the coast against pirates and smugglers, the fort’s granite walls and watchtowers once faced the mouth of Tung Chung Bay; it later housed police in the colonial years, fell into disrepair, and was restored so the city would remember what it once defended.

From town you can catch the cable strung to the clouds. Ngong Ping 360 lifts its cabins across the green ribs of Lantau; even at a distance you feel the pull to height. The promenade held the sunset like a plate, water rinsed in copper, cabins sliding along the horizon like beads. The old Tung Chung Pier turned scenic by patience alone, timber and tide agreeing on a slower clock.

Everywhere the island announced itself. The bridge arced into view, a steel grammar binding coasts. Planes lifted and descended with metronomic grace; the airport made this place a threshold, a must-pass, a vestibule between journeys. And yet few linger. The transit logic is strong, but if you stop, the town opens its drawers.

The taxis reminded me I was on Lantau: blue instead of urban red or New Territories green. Same fare language, different accent. The difference is the point, but the sameness is the comfort, another Hong Kong, tuned to island key.

Dusk made the choices simple. Shops faded to glow, the fort drew its trees closer, and the pier set a line for the last light. Somewhere a cable car emptied a cabin of laughter and quiet, somewhere a clerk counted the day’s receipts. The apology the airport carries, move along, keep going, thinned here, eased by mountains close at hand and streets that let you finish a sentence.

Why walk here. To feel a city pivot. Tung Chung is the joint where routes meet: terminal, cable, causeway, pier. In the turn, you find wide streets, local chatter, and a fort that remembers before schedules. The air comes salt and clean off Lantau’s ribs, the shops hum without hurry, and the blue cabs remind you you’re on island time, not mainland tempo.

Click for Adam’s diary for Day 18 challenge in Tai Po District!

Tai Po, a beginning held at the end

I started in Tai Po with mixed feelings. As I drove by the site of the fire, the phantom of char hung in the air, and the blackened walls kept the indelible scars of 2025 in plain sight. It is the first weekend of 2026, and it will linger.

I went first to Tai Mei Tuk, because some days you need the wide view. The Plover Cove dam drew its deliberate line across old salt, and the Eight Immortals Range Pat Sin Leng stood behind like elders keeping watch, ridges combed by wind, light braiding the slopes, so pretty it felt as if the mountains were breathing for the town. Wind lifted the kites, bike bells counted easy time, couples leaned on the rail and rehearsed a future in silhouettes. As scenic as it gets, yes, but not an escape. The beauty here is a counterweight, a place to set heaviness down without dropping it. The main dam of Plover Cove Reservoir, widely recognized as the world’s first major reservoir created by enclosing a sea inlet, was a 1960s promise poured in rock: turn brine to fresh, risk to steadiness, idea to daily cup. It is a lesson you can stand on, beginnings can be engineered.

As I moved to the next destination, Tai Po Industrial Estate slid by in a hush, the old engine room of Hong Kong working without applause. From bakeries proofing tomorrow’s bread to presses that once set the city’s morning in ink, from quiet labs to stubborn workshops, what we meet downtown was made here first, shaped in sheds and clean rooms along the river’s bend.

I turned toward Tai Po Waterfront Park and let the river take my steps. In every district I have visited, I have hunted the promenade; nowhere else lays out beauty so simply, a city giving you the shoreline like a front row seat.

Lawns widened into families and kites, pagodas stitched shade to susurrus. From the lookout tower, the contrast came clean: water like lacquer, paths in measured curves, and, in the same slow blink, the memory of recent loss somewhere across town. Tranquility and scar held in one frame, a reminder that grief is both shock and structure, first a wound, then a scaffold, then a room you can stand in again.

History threaded the afternoon without raising its voice. Tai Po Hui market has been a trading heart since the days when salt fields and ferries tied the New Territories to the harbor. Hakka farmers, fishers, and merchants converged here; the old market town grew into a junction where the railway stitched villages to the city and sent goods outward by the cartload. Today the covered market still hums with produce, dried goods, and cooked snacks, a living palimpsest of what the town eats and makes, and it is famously impossible to find parking anywhere close when it is busy.

The overcast folded the day into careful halves. The lookout tower drew its soft geometry; Tolo Harbour laid the sky back in its reflection. Somewhere a bench dried under the pagoda. Somewhere a child let go of a string and the kite remembered how to climb. The year turned its hinge audibly, click, and stayed open. And in that open space, small things gathered their courage: a stroller wheel ticking over brick, a flask shared at the rail, a laugh traveling a little farther than yesterday. The night did not erase the scars, but it made room beside them. Tomorrow felt a step closer.

Why walk here. Because Tai Mei Tuk gives you the breath to go on, and the park gives you the balance to hold what you have seen. Because a reservoir made from sea water proves that endurance can be designed. Because the Eight Immortals Range stands at your back while you face forward. Because Tai Po lets memory and hope share a bench without argument.

And this is where the loop closes. Eighteen districts walked, the last step landing like the first inhalation after a held breath. On the dam I jogged with a friend’s dog, her eager cadence pulling me toward the horizon, and I could not tell whether my breathlessness was exertion or the scene’s quiet immensity, a kind of secular numinousness that left the lungs unsure. Hong Kong is home, beautiful, resilient, rebuilding, bright. As I was gaping for breath at the edge of my long walk, I find myself falling in love with this city ever more. It is not an ending; it is a start written at the last stop, a city returning to itself with you inside the sentence. The future opens here, clear as the water, steady as the dam, and I trust it to rise higher still.

Together, we can inspire our community and empower young people through sports. Your generous donations will provide support to underprivileged youth and children in Hong Kong. Alongside IHKSports, we can work towards creating a healthier and more equitable society.

Why Donate?

Every donation, big or small, will motivate Adam to reach his goal of raising HK$50,000 for InspiringHK Sports Foundation. Your contributions will provide essential support to underprivileged youth and children in Hong Kong, offering them access to regular and professional sports opportunities.

Note: Donations of HK$100 or more will be eligible for a tax-deductible receipt upon request.

Together, we can make a difference!

Donors

- By Date

- By Amount

Yasmin Fong

Happy Birthday Ba! Thank you for doing this for IHK. Enjoy the romantic walks with 細隻妹

Yee Ka Erica Wong

Just make sure you win.

Kenneth Hui

Well done - Natalie and Ken

Yu Ichikawa

Good luck bro

Hei lok Wan

Add oil Adam and Charleen!! Have fun exploring the different districts!

Sy Chan

型

Matteo, Leo, Kait Caputi

Anonymous

Joanna Cheung

Ada Chan

Go Amy & UBS team!

HK$2,000

Yu Ting

3 days ago

Peggy Tong

Go sil!!

Patrick Lemouche

Go Adam go!

Anonymous

Anonymous

Kenneth Hui

Well done - Natalie and Ken

Yee Ka Erica Wong

Just make sure you win.

Denis & Bambi Tam & Wong

To our greatest sir adam, we support you fully ;)

Anonymous

Alan Yeung

Way to go!

Anonymous

Go Amy & UBS team!

HK$2,000

Yu Ting

3 days ago

Go Amy & UBS team!

HK$2,000

Yu Ting

3 days ago

Go Amy & UBS team!

HK$2,000

Yu Ting

3 days ago

Top Fundraiser(s)

Individual